For years, the U.S. de minimis rule reshaped American retail, manufacturing, and trade. Originally intended to simplify customs processing for travelers and small shipments, the rule evolved into a massive duty-free import channel: one increasingly used for commercial, direct-to-consumer e-commerce entering the U.S. under the $800-per-day threshold.

In 2025, that changed.

Beginning in May 2025 and expanding globally in August 2025, the United States suspended duty-free de minimis treatment for commercial shipments—first for China and Hong Kong, and then for all countries. The move marked one of the most significant trade-enforcement shifts in decades, with immediate ripple effects across global logistics networks.

This study examines what impact that decision has had so far.

Using the best publicly available data as of December 12, 2025, this report focuses on early, measurable outcomes. Most notably, the collapse in international postal traffic documented by the Universal Postal Union and the earlier air-cargo shock following the first phase of the suspension. While longer-term effects on U.S. manufacturing, employment, and investment will take time to appear in official economic data, the early evidence already suggests the rules governing ultra-low-cost imports into the United States are being rewritten in real time.

In a Nutshell

- The United States suspended duty-free de minimis treatment in two phases in 2025: first for China and Hong Kong in May, then globally in August, according to the White House.

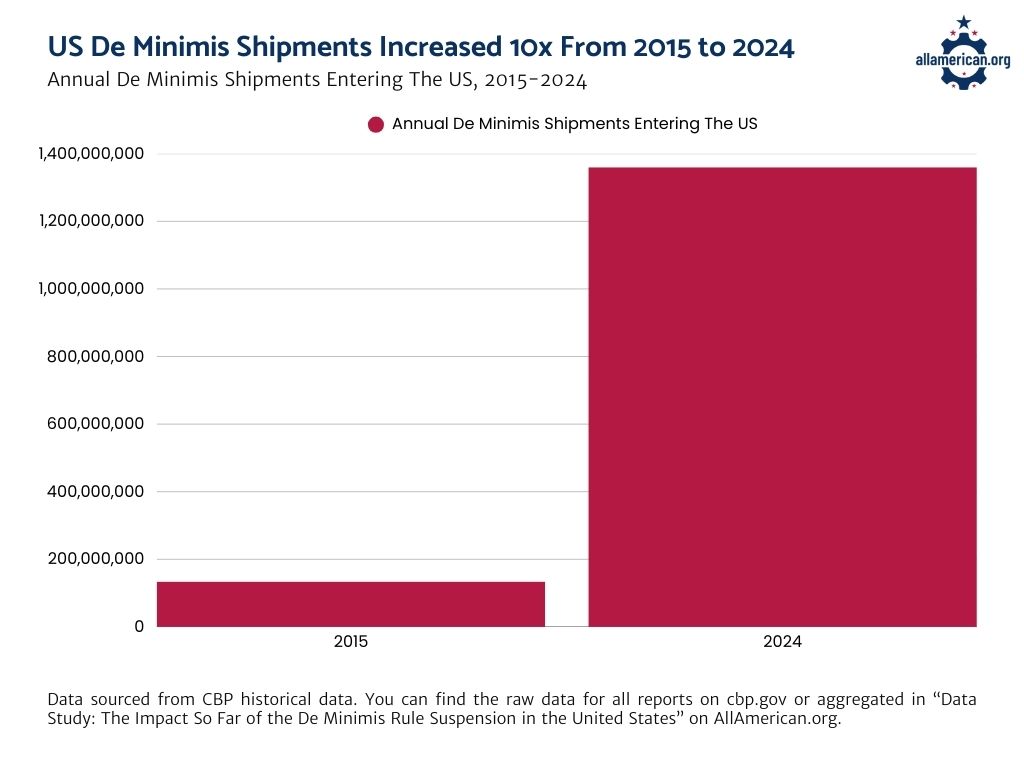

- Before the suspension, de minimis imports had grown to more than 1.36 billion shipments per year, making it one of the largest import channels into the United States by volume.

- The most immediate and measurable impact so far has been a sudden collapse in international postal shipments to the U.S. following the global suspension, with the Universal Postal Union reporting an 81% drop in inbound postal traffic week over week.

- Earlier changes targeting China and Hong Kong triggered sharp disruptions to air cargo capacity, revealing how dependent direct-ship e-commerce models were on duty-free entry.

- Early consumer-behavior data shows declining engagement with some ultra-low-cost import platforms following the rule changes, suggesting demand sensitivity even to partial enforcement shifts.

- For American manufacturers and U.S.-based brands, the suspension begins to narrow long-standing price and compliance disadvantages created by duty-free mass importing. However, full economic effects will take time to appear in official data.

- Significant data gaps remain, including how much additional duty revenue has been collected and how much trade has shifted into bulk imports or U.S. warehouses, as Customs and Border Protection has not yet released disaggregated post-suspension data.

- Even with those limitations, early evidence shows the de minimis suspension is already reshaping trade flows, logistics networks, and competitive dynamics in the U.S. market.

Why De Minimis Mattered (And Why It Became Impossible to Ignore)

For most of its history, the U.S. de minimis rule was obscure and largely uncontroversial.

Codified under Section 321 of the Tariff Act, the rule allows imports valued at $800 or less per person per day to enter the United States without paying duties or many traditional customs fees—a threshold that has been in place since 2016, when Congress raised it from $200, according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection. The intent was straightforward: reduce administrative burdens for travelers, small purchases, and genuinely low-risk shipments that were not worth the cost of formal processing.

For years, that is largely how the rule was used.

But over the past decade, the economics of global e-commerce (and the scale of direct-to-consumer shipping) changed dramatically.

By 2024, de minimis imports into the United States had exploded to more than 1.36 billion shipments per year, up from 134 million shipments in 2015, according to the White House. That growth transformed what was once a marginal customs provision into one of the largest import channels in the U.S. economy by volume.

Customs and Border Protection has stated that it processes more than four million de minimis shipments per day on average, often with only minimal information about the contents, origin, or seller (a figure echoed by the Congressional Research Service).

That scale mattered because the rule was never designed for it.

From Convenience to Competitive Distortion

As de minimis volumes surged, the rule increasingly benefited large overseas platforms shipping directly to U.S. consumers, rather than individuals making occasional purchases. Fast-fashion and ultra-low-cost marketplaces were able to route millions of individual packages into the U.S. each day without paying duties that domestic manufacturers and traditional importers routinely face.

For American-made brands (particularly in apparel, home goods, toys, and consumer products), this created a structural disadvantage. U.S. companies importing raw materials or finished goods in bulk paid duties, complied with extensive customs documentation requirements, and absorbed regulatory costs that many direct-ship foreign sellers avoided entirely.

The result was a price gap that had little to do with productivity or innovation, and everything to do with how goods entered the country.

Enforcement and Safety Concerns Followed the Scale

As de minimis volumes climbed, enforcement challenges became harder to ignore.

Federal agencies increasingly argued that the problem was not isolated bad actors, but scale. Customs and Border Protection was attempting to screen millions of low-value shipments per day, often with limited advance data; a task fundamentally different from inspecting traditional containerized or bulk imports.

The White House later summarized this concern by asserting that a disproportionate share of seizures related to narcotics, counterfeits, and unsafe products were tied to de minimis shipments, framing the channel as a growing enforcement and safety vulnerability rather than a low-risk convenience.

Whether or not one accepts every enforcement claim at face value, the underlying issue was structural. By this point, de minimis had already evolved far beyond its original purpose, creating significant enforcement challenges.

That reality set the stage for the policy shift that followed in 2025.

What Changed in 2025: From Loophole to Liability

The shift away from de minimis in 2025 did not happen all at once.

Instead, the United States moved in two distinct phases, each revealing just how deeply the rule had become embedded in global e-commerce and logistics networks.

Phase One: China and Hong Kong Lose De Minimis (May 2, 2025)

On May 2, 2025, the U.S. formally ended duty-free de minimis treatment for shipments originating from China and Hong Kong, citing national security concerns, trade enforcement failures, and the role of low-value imports in illicit trafficking.

This first phase was significant not because it eliminated de minimis entirely, but because it targeted the single largest source of low-value e-commerce shipments into the United States.

Prior reporting showed that nearly half of all air cargo shipments from China to the U.S. consisted of low-value e-commerce goods, underscoring how exposed those trade lanes were to any change in the rule, according to Reuters.

Almost immediately, logistics providers began adjusting. Reuters reported that average daily freighter capacity from China to the United States fell 39% in the first entire week after the May 2 change, reflecting a rapid collapse in demand for direct-ship e-commerce cargo.

At the time, some observers viewed the disruption as a narrow, China-specific shock. That assumption would not hold.

Phase Two: The Global Suspension (August 29, 2025)

On August 29, 2025, the United States expanded the suspension of duty-free de minimis treatment to all countries, transforming what had been a targeted enforcement action into a structural overhaul of how low-value goods enter the U.S. market, according to the White House.

Under the global change, commercial shipments that previously entered duty-free became subject to either:

- Origin-based tariff rates, reported to range from 10% to as high as 50%, or

- A flat-fee duty option, reported in the range of $80 to $200 per shipment, depending on the carrier and circumstances,

as described in coverage by the Associated Press.

While the policy preserved limited exemptions for personal gifts (up to $100) and personal souvenirs (up to $200), those carveouts were narrow and did not apply to the commercial e-commerce flows that had come to dominate de minimis usage.

The practical effect was immediate: millions of packages that had previously bypassed duties, tariffs, and much of the customs process were suddenly subject to costs and administrative requirements they had never faced before.

Why Implementation Proved So Disruptive

The severity of the disruption was not driven solely by higher costs. It was also a consequence of how de minimis shipments move through the system.

Customs and Border Protection has acknowledged that it processes more than four million de minimis imports per day, often with limited advance information compared to traditional imports, according to CBP reporting cited by STR Trade.

Postal operators and carriers, many of which had never been responsible for calculating or collecting U.S. duties on individual consumer parcels, were suddenly required to perform those functions on a massive scale.

International postal networks were particularly exposed. The global postal system had been optimized around duty-free delivery of low-value goods, not real-time tariff calculation and collection. As a result, the August 29 change did not merely slow shipments; it temporarily broke established routes.

Within days, dozens of foreign postal operators began suspending some or all mail services to the United States while scrambling to adapt, according to the Associated Press.

In effect, the de minimis rule did not just lower costs; it shaped the entire architecture of cross-border e-commerce. Removing it exposed how dependent that system had become on a regulatory assumption that no longer applied.

How Big the System Was Before the Shutdown

To understand why suspending de minimis treatment caused such an abrupt disruption, it’s necessary to grasp just how large the system had grown before any rules changed.

What began as a narrow trade facilitation tool had, by the mid-2020s, grown into one of the largest import pipelines into the United States: by sheer package count, not dollar value.

According to the White House, annual de minimis shipments entering the U.S. grew from 134 million in 2015 to more than 1.36 billion in 2024, an increase of more than 900% in less than a decade.

Put differently, de minimis traffic went from being a rounding error in U.S. trade statistics to a billion-package-per-year system operating primarily outside the traditional customs framework.

Millions of Packages Every Single Day

Customs and Border Protection has stated that it processes more than four million de minimis shipments per day on average, a figure echoed by the Congressional Research Service.

That daily volume helps explain why even small procedural changes can ripple across the entire system. Unlike containerized imports, which arrive in predictable batches and move through a limited number of ports, de minimis shipments arrive as a constant, decentralized flow through airports, postal facilities, and express-carrier hubs nationwide.

The system was designed for speed, not scrutiny.

Why Scale Changed the Risk Profile

At low volumes, duty-free treatment for small parcels made administrative sense. At the billion-package scale, the same rule created structural blind spots.

CBP has acknowledged that de minimis shipments often arrive with limited advance data, making it more challenging to assess origin, contents, or compliance risk before arrival. Screening millions of packages per day under those conditions is fundamentally different from inspecting bulk imports supported by detailed manifests, importer records, and customs bonds.

As a result, enforcement capacity did not scale in proportion to volume.

The White House has argued that this imbalance allowed counterfeit goods, unsafe products, and illicit substances to move through the de minimis channel at disproportionately high rates; an argument that became central to the case for suspension.

Why Package Count Matters More Than Dollar Value

While de minimis shipments are, by definition, low in individual value, their cumulative impact is significant.

A billion shipments represent:

- A billion separate customs decisions

- A billion potential enforcement touchpoints

- And (critically for U.S. manufacturers), a billion opportunities for duty-free competition against domestically produced goods

For American companies that manufacture or assemble products in the United States, the competitive issue was not the occasional small import. It was the normalization of mass commercial importing under a rule never designed for mass commerce.

By 2024, de minimis was no longer a side channel in U.S. trade. It was a parallel system large enough that shutting it down, even partially, was bound to produce immediate and visible effects.

Let’s take a look at the first place where those effects became unmistakable: international postal flows, where the impact of the global suspension showed up almost overnight.

The First Measurable Impact: A Sudden Collapse in Postal Imports

The clearest and most immediate evidence that suspending de minimis materially changed U.S. import flows did not come from customs revenue reports or quarterly trade statistics. It came from the global postal system.

Within days of the August 29, 2025, global suspension, international postal shipments to the United States fell off a cliff.

The Universal Postal Union (UPU), which tracks item-level postal flows across national postal operators worldwide, reported an 81% decrease in inbound postal traffic to the United States on Friday, August 29, compared to Friday, August 22, just one week earlier.

This was not a gradual slowdown or seasonal fluctuation. It was an abrupt break.

Why Postal Channels Were Hit First (and Hardest)

International mail had become one of the primary arteries for de minimis shipments, particularly for ultra-low-value, direct-to-consumer goods. Postal delivery offered foreign sellers the lowest-cost and least complex way to reach American buyers, often with minimal customs friction.

When the de minimis suspension took effect globally, postal operators were suddenly required to calculate, collect, or account for U.S. duties on millions of individual parcels; a function the international postal system was never designed to perform at that scale.

The UPU notes that inbound mail to the United States accounts for approximately 15% of all global postal traffic, underscoring how central the U.S. market is to international mail networks (UPU). Over the prior 12 months, that inbound traffic originated roughly:

- 44% from Europe

- 30% from Asia

- 26% from the rest of the world

In other words, the disruption was not limited to one country or region: it was global.

Postal Service Suspensions Around the World

As postal operators struggled to adapt, the disruption quickly became visible to consumers.

According to reporting citing UPU statements, 88 postal operators informed the organization that they had suspended some or all postal services to the United States in the days following the rule change, as carriers paused shipments while attempting to implement duty-collection solutions.

Those suspensions included operators in 78 United Nations member states, along with nine additional territories, highlighting the extraordinary scope of the breakdown.

In practical terms, “suspension” meant that consumers in dozens of countries could no longer send standard parcels to the United States, and U.S. consumers ordering goods from abroad saw shipments delayed, canceled, or returned to senders.

Why This Metric Matters

Postal traffic is not the only way goods enter the United States, but it is one of the most sensitive indicators of de minimis activity.

Because postal channels are disproportionately used for low-value, direct-to-consumer imports, a sudden collapse in mail volumes is a strong signal that the underlying economic model changed. Sellers who relied on duty-free postal delivery could no longer operate under the same cost assumptions, and many chose to pause shipments rather than absorb or navigate the new requirements.

Notably, this decline occurred before any comprehensive government reporting on duties collected, clearance times, or rerouted trade was available. In that sense, postal data provided an early, independent confirmation that the de minimis suspension was not symbolic; it was operationally disruptive.

The following section examines a related but earlier signal of stress in the system: what happened to air cargo and logistics networks after China and Hong Kong lost de minimis treatment months earlier.

The Earlier Shock: What We Saw After China and Hong Kong Lost De Minimis

The global suspension of de minimis treatment in August produced the most dramatic and visible disruption, but it was not the first warning.

Months earlier, when the United States ended duty-free de minimis treatment for China and Hong Kong on May 2, 2025, the first shock waves appeared not in postal data, but in air cargo markets.

At the time, the change was widely viewed as a targeted enforcement action. In practice, it functioned as a stress test for the entire direct-ship e-commerce model.

Why China-to-U.S. Trade Was Uniquely Exposed

Before May 2025, China was the dominant origin point for de minimis shipments entering the United States, particularly for fast fashion, electronics accessories, home goods, and other low-cost consumer products.

According to Reuters, “almost half” of all air cargo shipments from China to the United States consisted of low-value e-commerce goods, highlighting how deeply de minimis was embedded in those trade lanes.

Major platforms built logistics systems around this environment, relying on speed rather than shipping efficiency to move millions of individual packages directly from overseas factories to U.S. consumers.

Reuters reported that Temu and Shein together were shipping roughly 9,000 metric tons of cargo per day worldwide, equivalent to about 88 Boeing 777 freighters, based on estimates from freight analytics firm Xeneta.

That level of volume left little margin for policy change.

A Rapid Drop in Air Cargo Capacity

When duty-free de minimis treatment ended for China and Hong Kong, demand for direct-ship air freight fell sharply.

Average daily freighter capacity from China to the United States declined 39% in the first full week after May 2, compared to the prior week.

That contraction was significant not only for airlines and logistics providers, but as a broader economic signal. Air freight is one of the most expensive ways to move goods internationally. If sellers could no longer rely on duty-free entry, the economics of shipping millions of low-margin packages by air deteriorated almost immediately.

What the Air Cargo Shock Revealed

The May 2 disruption exposed a critical realization: the de minimis rule did not simply reduce costs; it enabled an entire logistics strategy.

Direct-to-consumer shipping from overseas factories to U.S. households worked at scale because:

- Duties were avoided

- Customs processing was minimal

- Speed mattered more than shipping efficiency

Once duties were applied (even selectively), the model began to unravel.

Some sellers paused shipments altogether. Others explored rerouting goods through third countries, shifting to bulk imports, or placing inventory inside U.S. warehouses. At the time, there was no public data quantifying how much trade shifted versus disappeared, but the collapse in air cargo demand made one point unmistakable: the prior volume was not resilient to policy change.

A Preview of What Would Come Next

In hindsight, the China and Hong Kong phase offered a preview of the global suspension that followed.

The May 2 shock demonstrated that de minimis was not a marginal trade preference: it was a load-bearing feature of cross-border e-commerce. Removing it, even partially, produced immediate, measurable changes in logistics behavior.

When the rule was later suspended globally in August, the impact expanded beyond air cargo into international postal networks, revealing just how much of the system (across regions and transport modes) had been built around the assumption of duty-free entry.

Okay, let’s turn from supplier logistics to the consumer side of the equation, examining early behavioral signals that show how shoppers themselves responded as the economics of ultra-low-cost imports began to change.

Consumer Behavior Signals: Are Shoppers Responding?

Logistics disruptions tell one part of the story. Consumer behavior tells another.

While comprehensive post-suspension retail sales data is not yet available, early platform usage and engagement metrics offer an important proxy for how American consumers responded once the economics of ultra-low-cost imports began to change.

So far, the clearest signal comes from marketplace-level data.

A Sharp Drop in Ultra-Low-Cost Marketplace Engagement

Daily active users on Temu’s U.S. platform fell 48% in May 2025 compared to March, based on data from analytics firm Sensor Tower.

The decline closely followed the May 2 removal of de minimis treatment for China and Hong Kong, suggesting that even a partial rollback of duty-free entry altered consumer engagement patterns.

Over the same period, Shein’s U.S. usage proved more resilient, but Reuters noted that Temu’s drop was especially pronounced, reflecting its heavier reliance on ultra-low prices and direct shipping from overseas factories.

Notably, this decline occurred before the global suspension in August, indicating that the de minimis loophole played a central role in sustaining engagement on the most price-sensitive platforms.

Why Engagement Data Matters (And Its Limits)

Marketplace usage metrics are not a direct substitute for import-volume data. A decline in daily users does not automatically translate to a proportional decline in shipments.

Consumers may:

- Consolidate purchases

- Shop less frequently but in larger orders

- Shift to different platforms or sellers

That said, engagement data remains valuable because it captures behavioral sensitivity to price and friction.

Platforms built on ultra-low margins depend on high-frequency, impulse-driven purchasing. When landed costs rise, even modestly, or delivery becomes less predictable, that behavior changes quickly.

In this sense, falling engagement aligns with what logistics data already showed: once duty-free assumptions disappeared, the direct-ship model lost much of its economic advantage.

Price Sensitivity and the End of “Invisible” Costs

For years, many consumers experienced de minimis imports as artificially cheap, with duties effectively hidden by policy rather than efficiency.

The suspension exposed those costs.

Under the new regime, low-value shipments can face origin-based tariffs reportedly ranging from 10% to 50%, or flat fees reported between $80 and $200 per shipment, depending on the carrier and import channel, according to Associated Press reporting.

Even when sellers absorb part of those costs, the economics of shipping a $10 or $15 item directly from overseas to a U.S. consumer change dramatically.

As a result, purchases that once felt “too cheap to pass up” often no longer make sense once duties, delays, or uncertainty are introduced.

What We Can and Cannot Conclude So Far

At this stage, consumer response data should be interpreted carefully.

What the data supports:

- Engagement with the most price-sensitive, de minimis-dependent platforms declined after policy changes.

- Consumer demand for ultra-low-cost, direct-ship imports appears highly sensitive to even partial enforcement shifts.

What the data does not yet support:

- A precise estimate of reduced import volumes

- A clear measurement of substitution toward American-made goods

- Long-term changes in consumer preferences

Those answers will require additional time and broader datasets.

Still, when viewed alongside collapsing postal traffic and shrinking air cargo demand, early consumer behavior signals reinforce a central conclusion: the suspension of de minimis altered incentives for both sellers and buyers almost immediately.

Enforcement and safety are the next big topics to talk about, examining why the federal government ultimately acted and how those concerns shaped the policy’s design.

Enforcement, Safety, and Why the Government Acted

By the time the de minimis suspension was announced, the policy debate was no longer centered solely on trade fairness or domestic manufacturing. Enforcement and public safety concerns had moved to the forefront of the government’s justification.

The White House framed the suspension as a response to what it described as systemic enforcement failures tied directly to the scale and structure of de minimis imports, arguing that the channel had become a high-risk pathway rather than a low-risk convenience.

The Government’s Core Claim: Scale Overwhelmed Oversight

According to the administration, the sheer volume of low-value shipments entering the United States had outpaced the country’s ability to screen them effectively.

The White House has stated that:

- 90% of cargo seizures originated as de minimis shipments

- 98% of narcotics seizures came through de minimis channels

- 97% of intellectual property rights seizures were tied to de minimis imports

- 77% of health-and-safety seizures originated in de minimis shipments

The same fact sheet stated that these seizures included 31 million counterfeit items and 20 million dangerous or unsafe products, figures the administration used to argue that de minimis had become a disproportionately risky import channel.

These numbers reflect government assertions rather than independently audited totals, but they are central to understanding how federal enforcement agencies internally assessed the problem.

Why De Minimis Was Structurally Hard to Police

Even critics of the administration’s framing generally agree on one point: de minimis shipments are uniquely difficult to screen at scale.

Customs and Border Protection has acknowledged that it processes more than four million de minimis imports per day, often with only minimal advance data about the shipment’s contents, value, or seller, according to CBP reporting cited by STR Trade.

Unlike traditional imports, de minimis shipments typically:

- Do not require a formal customs entry

- Often arrive without a licensed customs broker

- Involve individual consumers rather than established importers of record

- Provide limited data for pre-arrival risk targeting

At huge package volumes, these characteristics create enforcement blind spots that cannot be solved simply by inspecting more boxes.

Enforcement Concerns Extended Beyond Counterfeits

While counterfeit goods frequently dominate headlines, enforcement agencies have pointed to broader categories of risk associated with de minimis imports.

Those concerns include:

- Unsafe consumer products that bypass regulatory compliance checks

- Goods violating U.S. health, labeling, or safety standards

- Illicit substances concealed within small parcels

- Products misdeclared to evade tariffs or origin rules

The administration argued that de minimis effectively allowed large volumes of commercial goods to enter the country outside the enforcement guardrails applied to nearly all other imports, undermining both safety and trade compliance.

Enforcement as a Secondary but Decisive Driver

It is important to note that enforcement concerns did not exist in isolation. They reinforced (and were reinforced by) complaints from U.S. manufacturers, retailers, and trade groups who argued that de minimis created unfair competitive conditions.

In that sense, enforcement became the decisive argument that pushed the issue from policy debate to action. Closing the de minimis loophole was no longer framed primarily as an economic or protectionist measure, but as a necessary correction to a system.

These policy changes obviously have real-world implications, so let’s examine what these changes mean for American manufacturers and U.S.-based brands so far, and where the benefits and limitations are beginning to emerge.

What This Means for American Manufacturers (So Far)

For U.S. manufacturers and American-made brands, the suspension of de minimis treatment represents something they have not had in years: a structural change that alters the rules of competition rather than asking domestic producers to compete around them.

While it is far too early to declare clear winners and losers, early evidence shows the policy has begun to unwind some of the policy-driven advantages that de minimis-enabled import models enjoyed over domestic production.

Narrowing a Price Gap That Was Never Market-Driven

For years, many American manufacturers were not competing against foreign producers on productivity, quality, or innovation. They were competing against a regulatory exemption.

Domestic manufacturers pay duties on imported inputs, comply with U.S. labor and safety laws, meet regulatory and labeling standards, and ship products within the United States using domestic logistics networks. At the same time, millions of foreign-made consumer goods entered the U.S. market duty-free, often bypassing costs that U.S.-based producers had no way to avoid.

By suspending duty-free treatment for low-value commercial shipments, the de minimis reform directly targets that imbalance.

Low-value imports that once entered the United States with zero duty liability are now subject to origin-based tariffs or flat fees, fundamentally changing the economics of shipping a $5, $10, or $20 item directly from overseas.

For American manufacturers, that shift does not guarantee competitiveness, but it removes a distortion that had nothing to do with efficiency.

Speed, Reliability, and the Domestic Advantage

The suspension also reshapes how speed and reliability factor into purchasing decisions.

Direct-ship import models relied heavily on air freight and postal delivery to compensate for long distances. When those channels were disrupted by higher costs, service suspensions, or longer clearance times, the advantage shifted toward sellers with inventory already in the United States.

Domestic manufacturers and U.S.-based brands do not face international customs clearance delays, overseas postal suspensions, or tariff uncertainty. As international postal imports collapsed by 81% immediately after the global suspension, the reliability gap became visible almost overnight.

For buyers (especially businesses, institutions, and repeat consumers), predictability often matters as much as price.

Sectors Most Exposed to Change

Not all U.S. manufacturers are affected equally.

The de minimis loophole disproportionately impacted industries where:

- Products are lightweight and inexpensive

- Price sensitivity is high

- Quality, safety, or compliance are difficult to assess before purchase

Those sectors include:

- Apparel and fast fashion

- Home goods and décor

- Toys and children’s products

- Consumer electronics accessories

- Health and safety-sensitive consumer goods

These same categories feature prominently in de minimis enforcement actions cited by the White House, reinforcing the overlap between trade distortion and safety concerns.

In these industries, even modest cost increases on imported goods can materially alter competitive dynamics.

What the Data Does Not Yet Show

Despite early structural changes, current data does not yet show:

- A measurable increase in U.S. manufacturing output

- Documented employment gains attributable to the suspension

- A quantified shift in consumer spending toward American-made goods

Those outcomes take time and depend on broader economic conditions, including inflation, interest rates, and overall consumer demand.

What the data does show is a meaningful change in the cost and feasibility of bypassing the U.S. trade system: a necessary, though not sufficient, condition for domestic manufacturing to compete on more equal footing.

A Structural Change, Not a Short-Term Fix

For American manufacturers, the significance of de minimis reform lies less in immediate sales gains and more in the restoration of basic trade discipline.

When imports face the same baseline requirements (duties, declarations, and enforcement scrutiny), the competitive landscape begins to reflect real differences in cost structures and capabilities, rather than regulatory loopholes.

Whether that shift ultimately leads to reshoring, expanded domestic production, or stronger U.S.-based supply chains will depend on what happens next.

Who Benefits, Who Bears the Cost

The suspension of de minimis treatment did not simply help one group and harm another. Instead, it reshuffled incentives across the trade system, producing clear beneficiaries, newly exposed costs, and unavoidable tradeoffs.

Understanding those dynamics is essential to evaluating the policy honestly.

American Manufacturers and Domestic Brands

For U.S.-based manufacturers and American-made brands, the primary benefit is structural rather than immediate.

By ending duty-free treatment for low-value commercial imports, the suspension reduces a long-standing regulatory asymmetry. Domestic producers have always operated within the U.S. trade, labor, and regulatory system. De minimis allowed many foreign sellers to compete in the U.S. market while bypassing that framework entirely.

Early logistics data suggests the policy materially altered that dynamic. The collapse in international postal imports and the contraction in direct-ship air cargo indicate that some of the lowest-cost import pathways are no longer economically viable at scale.

For American-made companies, this does not guarantee increased sales, but it does reduce the frequency with which they are undercut by products priced below realistic production and compliance costs.

Consumers: Lower Prices vs. Fewer Shortcuts

Consumers are both beneficiaries and cost-bearers.

For years, de minimis enabled ultra-low prices by shifting costs away from buyers and onto the policy framework itself. Duties were avoided, compliance costs were externalized, and delivery delays were normalized.

With the suspension in place, some consumers now face:

- Higher landed prices

- Fewer ultra-low-cost options

- Longer delivery times or canceled shipments

At the same time, consumers may benefit from:

- Improved product safety and regulatory compliance

- Reduced exposure to counterfeit goods

- More predictable delivery from U.S.-based sellers

The tradeoff is straightforward: fewer artificially cheap imports in exchange for a market that more accurately reflects actual costs.

Marketplaces and Foreign Direct-Ship Platforms

Platforms built around duty-free, direct-to-consumer imports face the most immediate disruption.

Engagement data showing sharp declines on some ultra-low-cost marketplaces following the China and Hong Kong phase suggests these platforms are highly sensitive to even partial enforcement changes.

In response, many platforms have begun adjusting by:

- Raising prices

- Absorbing some duties

- Shifting inventory into U.S. warehouses

- Exploring bulk import or third-country routing strategies

Each adjustment increases cost and reduces the advantage that de minimis once provided.

Carriers, Postal Operators, and Customs Brokers

The global postal system absorbed much of the immediate shock.

Following the global suspension, dozens of foreign postal operators temporarily suspended service to the United States, highlighting how unprepared the system was for large-scale duty calculation and collection.

Commercial carriers and customs brokers, while better equipped to handle duties, also face higher administrative burdens as millions of shipments that once bypassed formal entry now require additional processing.

Over time, these sectors may benefit from clearer rules and more predictable flows, but the transition has been costly.

Small Businesses That Relied on Low-Value Imports

Not all affected businesses are large foreign platforms.

Some U.S. small businesses relied on de minimis imports for:

- Components

- Promotional items

- Low-cost resale goods

For these businesses, the suspension raises costs and complexity, particularly for firms that lack the capabilities to shift quickly to bulk imports or domestic sourcing.

This highlights an important reality: closing a loophole can still impose real adjustment costs, even when the long-term objective is fairer competition.

A System Rebalanced, Not Simplified

The de minimis suspension did not eliminate trade—it changed how trade happens.

It now favors:

- Sellers with inventory inside the United States

- Companies already complying with trade and safety rules

- Business models built around scale, compliance, and predictability

It disadvantages:

- Ultra-low-margin, direct-ship import models

- Systems optimized around duty-free assumptions

- Sellers dependent on frictionless international postal delivery

Whether this rebalancing ultimately strengthens U.S. manufacturing depends on how the system evolves next, both domestically and globally.

How the U.S. Now Compares to the Rest of the World

While the 2025 suspension of de minimis treatment marked a major shift for the United States, it did not occur in a vacuum. In fact, many advanced economies had already spent years grappling with the same problem: how to manage exploding volumes of low-value imports without undermining domestic industries, tax systems, and enforcement capacity.

Seen in that context, the U.S. move was less radical than overdue.

Europe: Closing the Same Loophole in Stages

The European Union offers the closest comparison in both size and complexity.

For years, the EU allowed low-value goods to enter with limited friction, similar to the U.S. approach. But as cross-border e-commerce volumes surged, European policymakers moved earlier to tighten controls.

In 2021, the EU eliminated its VAT exemption for low-value imports (€22), meaning all imported goods are now subject to value-added tax regardless of price, even when customs duties do not apply, according to the European Commission. To manage compliance, the EU introduced the Import One Stop Shop (IOSS), requiring sellers or marketplaces to register and remit VAT on goods valued up to €150.

What remained (and is now being dismantled) is the EU’s customs duty exemption for goods under €150.

In 2025, EU institutions agreed to abolish that threshold as part of a broader customs reform package, with implementation beginning in 2026, according to both the European Commission and the Council of the EU.

The size of the challenge mirrors the U.S. experience. Reuters reported that more than 4.6 billion low-value parcels entered the EU in 2024, with over 90% originating from China, overwhelming customs authorities and domestic retailers.

As an interim measure, the EU has agreed to impose a €3 duty on low-value e-commerce parcels starting July 1, 2026, while full reforms are phased in.

Other Countries Moved Even Earlier

The United States was also late relative to several smaller economies that acted years ago.

- Australia began applying its 10% Goods and Services Tax (GST) to low-value imported goods in 2018, covering goods valued at AUD 1,000 or less (ATO guidance; ABF overview).

- New Zealand followed in 2019, requiring overseas sellers and marketplaces to collect GST on low-value imports up to NZ$1,000, provided registration thresholds are met (NZ Inland Revenue guidance; NZ policy paper).

- Norway abolished its VAT exemption for low-value imports effective January 1, 2024, removing the previous NOK 350 threshold (Posten overview; WCO analysis).

- Türkiye sharply reduced its simplified import threshold from €150 to €30 in 2024 and increased duty rates on low-value e-commerce shipments, particularly from non-EU countries (EY tax alert; DHL summary).

- Vietnam eliminated its duty exemption for low-cost imports valued under approximately $40 beginning in February 2025, citing harm to domestic producers and tax leakage (Reuters Vietnam reporting).

Even Canada, which still maintains limited low-value thresholds, applies far lower caps than the U.S. historically did, with duties generally applying above CA$150 and taxes above CA$40, according to trade-services analyses.

What Makes the U.S. Shift Distinct

Despite global convergence, the U.S. approach stands out in two important ways.

First, the scale is unmatched. Before the suspension, the U.S. processed more than 1.36 billion de minimis shipments annually, a volume that rivals or exceeds the entire volume processed by customs systems elsewhere.

Second, the speed of impact has been unusually visible. The immediate collapse in international postal traffic following the global suspension contrasts with the more gradual transitions seen in other countries, where VAT or duty reforms were phased in over several years.

In that sense, the U.S. experience now serves as an early case study (both cautionary and instructive) for how deeply low-value import exemptions can become embedded in modern commerce.

What We Still Can’t Measure (Yet)

Despite the clear disruptions observed in logistics, postal flows, and consumer engagement, some of the most important questions surrounding the de minimis suspension remain unanswered. Not because they are unimportant, but because the data does not yet exist in a usable public form.

Being explicit about these gaps is essential to understanding both what this study can conclude and where caution is still required.

How Much Duty Revenue the Suspension Has Generated

One of the most obvious questions is also the hardest to answer: how much additional duty revenue has the U.S. collected as a result of suspending de minimis treatment?

As of December 12, 2025, there is no publicly released dataset from U.S. Customs and Border Protection that:

- Separates duties collected on former de minimis shipments from other imports

- Distinguishes between revenue generated by the May 2 China/Hong Kong phase and the August 29 global suspension

- Aggregates collections across postal, express carrier, and commercial entry channels

CBP publishes general trade and e-commerce information, but it does not yet provide a breakdown that isolates the fiscal impact of the de minimis suspension itself.

Without that data, any estimate of revenue gains would be speculative, and this study avoids speculation.

Changes in Customs Clearance Times

Another critical unknown is how the suspension has affected customs clearance times.

Anecdotally, importers, carriers, and consumers have reported delays following the August 29 change, particularly within postal channels. However, there is no authoritative, system-wide dataset showing:

- Average clearance time increases for former de minimis shipments

- Differences in processing times between postal, express, and bulk import channels

- Whether observed delays are temporary implementation issues or structural changes

Until CBP or carriers release aggregated performance metrics, these effects remain difficult to quantify reliably.

How Much Trade Has Rerouted (And Where It Went)

Perhaps the most consequential unanswered question is how much trade disappeared versus how much simply moved.

Public data does not yet show:

- What share of former de minimis shipments shifted to bulk imports

- How much inventory moved into U.S.-based warehouses

- Whether rerouted imports now enter under different tariff classifications

- How much trade volume was permanently lost due to higher costs

Early indicators, such as the collapse in international postal traffic and reduced air cargo demand, confirm significant disruption. What they do not reveal is the final destination of that trade.

Answering these questions would likely require:

- Carrier-level shipment data

- Customs broker filings

- Importer-of-record panels

- Marketplace disclosures that are not publicly available

Manufacturing and Employment Effects Take Time

Finally, it is too early to draw firm conclusions about manufacturing output, reshoring, or job creation.

Even if the de minimis suspension improves competitive conditions for U.S. manufacturers, translating that shift into:

- Expanded production

- New hiring

- Capital investment

takes time. Often measured in years, not months.

Traditional indicators such as industrial production, employment data, and sector-level output statistics will lag well behind the policy change itself.

Why These Gaps Matter

These limitations do not weaken the findings of this study. Instead, they define its scope.

The data clearly shows that suspending de minimis treatment:

- Disrupted established import channels

- Altered logistics economics

- Changed incentives for sellers and consumers

What it does not yet show is the full downstream economic outcome.

That distinction matters. Overstating short-term effects would be as misleading as ignoring early signals altogether.

What Comes Next: How We’ll Track the Long-Term Impact

The suspension of de minimis treatment did not end a debate; it began a new phase of it.

This study shows that the policy has already altered behavior. Logistics flows shifted. Postal imports collapsed. Direct-ship economics changed. Consumer engagement responded. These outcomes are measurable, observable, and difficult to dismiss as noise.

What remains unresolved is whether those early disruptions translate into lasting structural change.

The Data That Will Matter Most Going Forward

To evaluate the long-term impact of the de minimis suspension, particularly for American manufacturing, several datasets will be critical.

Among the most important:

- Customs revenue data that isolates duties collected from former de minimis shipments, broken out by channel and country of origin, from U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

- Clearance-time metrics showing whether delays normalize as systems adapt, or whether higher friction becomes permanent for low-value imports.

- Import composition data revealing whether trade has rerouted into bulk shipments, shifted into U.S. warehouses, or moved to alternative sourcing countries.

- Manufacturing indicators, including production, employment, and investment data in sectors most affected by low-value imports.

Until these data points are publicly available and consistently reported, conclusions about economic outcomes must remain provisional.

A Structural Test, Not a Temporary Disruption

One of the most important questions ahead is whether the de minimis suspension proves durable.

If enforcement remains consistent, the policy could:

- Encourage inventory placement inside the United States

- Reward compliance-based business models

- Reduce the artificial cost advantage of ultra-low-value imports

- Strengthen the competitive position of American manufacturers over time

If enforcement weakens (or if new exemptions proliferate), the system could gradually revert to the dynamics that existed before 2025.

In that sense, the suspension is not a single policy decision so much as a stress test of the U.S. trade system’s willingness to enforce its own rules at scale.

Why This Matters for American Manufacturing

For U.S. manufacturers, the significance of de minimis reform lies in its potential to restore normal economic signals.

Manufacturing investment decisions depend on predictability. When imported goods bypass duties and enforcement, domestic producers are forced to compete against prices that do not reflect real costs. When that distortion is removed, competition begins to reflect productivity, quality, speed, and reliability instead.

Whether that shift ultimately leads to reshoring, expanded domestic capacity, or stronger U.S.-based supply chains will depend on factors well beyond trade policy alone. But without addressing de minimis, those outcomes were far less likely.

How We Will Continue Tracking This Issue

This study represents a snapshot, not a final verdict.

As new data becomes available, we will continue to:

- Track enforcement outcomes and trade flows

- Monitor impacts on American manufacturers and domestic brands

- Update readers as additional evidence emerges

- Compare U.S. outcomes with parallel reforms abroad

The de minimis suspension is one of the most consequential and least understood trade policy changes of the past decade. Its full impact will take time to unfold.

What is already clear is this: the era of frictionless, duty-free mass imports into the United States is no longer guaranteed, and that shift alone is reshaping the competitive landscape for American manufacturing.

References

Associated Press. (2025, August). Global mail to U.S. disrupted after de minimis rule change. https://apnews.com/article/d74eb6022e8838f39bba8ed9588c74ba

Australian Border Force. (n.d.). GST on low value imported goods. https://www.abf.gov.au/importing-exporting-and-manufacturing/importing/cost-of-importing-goods/gst-and-other-taxes/gst-on-low-value-goods

Australian Taxation Office. (n.d.). GST on low value imported goods. https://www.ato.gov.au/businesses-and-organisations/international-tax-for-business/gst-for-non-resident-businesses/gst-on-low-value-imported-goods

Congressional Research Service. (2024). Section 321 de minimis imports: Background and policy issues. https://www.everycrsreport.com/reports/R48380.html

Council of the European Union. (2025, November 13). Customs council takes action to tackle the influx of small parcels. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2025/11/13/customs-council-takes-action-to-tackle-the-influx-of-small-parcels/

DHL. (2024). Türkiye import duty changes for B2C e-commerce shipments. https://www.dhl.com/discover/en-tw/ship-with-dhl/export-with-dhl/turkey-import-duty-2024

Ernst & Young (EY). (2024). Türkiye reduces allowed value limits and increases duties applicable to B2C e-commerce shipments. https://www.ey.com/en_gl/technical/tax-alerts/turkiye-reduces-allowed-value-limits-on-and-increases-duties-applicable-to-b2c-e-commerce-shipments

European Commission. (n.d.). VAT One Stop Shop (OSS). https://vat-one-stop-shop.ec.europa.eu/index_en

European Commission. (2025, November 13). €150 customs duty exemption threshold to be removed in 2026. https://taxation-customs.ec.europa.eu/news/e-commerce-150-eur-customs-duty-exemption-threshold-be-removed-2026-2025-11-13_en

Inland Revenue Department (New Zealand). (n.d.). GST for overseas businesses. https://www.ird.govt.nz/gst/gst-for-overseas-businesses/gst-on-low-value-imported-goods

Inland Revenue Department (New Zealand). (n.d.). What GST is. https://www.ird.govt.nz/gst/what-gst-is

New Zealand Treasury & Inland Revenue. (2019). GST on low-value imported goods. https://taxpolicy.ird.govt.nz/-/media/project/ir/tp/publications/2019/2019-sr-gst-low-value-imported-goods/2019-sr-gst-low-value-imported-goods-pdf.pdf

Norwegian Post (Posten). (n.d.). Receiving goods from abroad: Customs rules. https://www.posten.no/en/customs/receiving-from-abroad/need-to-know-when-shopping-online-from-abroad

Reuters. (2025, February 7). U.S. Postal Service suspends shipments from China and Hong Kong after tariffs. https://www.reuters.com/world/us/us-post-office-suspends-shipments-china-hong-kong-after-trump-tariffs-2025-02-07/

Reuters. (2025, May 12). Trump tariffs hit air cargo demand, new challenge for Boeing and Airbus. https://www.reuters.com/world/us/trump-tariffs-hit-air-cargo-demand-new-challenge-boeing-airbus-2025-05-12/

Reuters. (2025, June 2). Temu daily U.S. users almost halved in May as Shein users rise, Sensor Tower says. https://www.reuters.com/world/us/temu-daily-us-users-almost-halved-may-shein-users-rise-sensor-tower-says-2025-06-02/

Reuters. (2025, January 4). Vietnam to scrap tax exemption for low-cost imports from February. https://www.reuters.com/markets/asia/vietnam-scrap-tax-exemption-low-cost-imports-feb-2025-01-04/

Reuters. (2025, May 21). EU eyes handling fee on online parcels in customs reform push. https://www.reuters.com/business/retail-consumer/eu-eyes-2-euro-handling-fee-online-parcels-customs-reform-2025-05-21/

Reuters. (2025, December 12). EU to impose duty on small e-commerce parcels starting July 2026. https://www.reuters.com/world/china/eu-impose-3-euro-duty-small-e-commerce-parcels-july-2026-2025-12-12/

STR Trade Report. (2025). CBP proposes rule changes on de minimis shipments. https://www.strtrade.com/trade-news-resources/str-trade-report/trade-report/january/cbp-proposes-rule-changes-on-de-minimis-shipments

Thomasnet. (n.d.). De minimis shipments explained. https://www.thomasnet.com/insights/de-minimis-shipments/

Universal Postal Union. (2025). FAQ: Impact of recent U.S. customs regulation changes on international postal services. https://www.upu.int/en/postal-solutions/technical-solutions/products/faq-impact-of-recent-us-customs-regulation-changes-on-international-postal-services

U.S. Customs and Border Protection. (n.d.). E-commerce and Section 321 de minimis imports. https://www.cbp.gov/trade/basic-import-export/e-commerce

White House. (2025, April). Fact sheet: President Donald J. Trump closes de minimis exemptions to combat China’s role in America’s synthetic opioid crisis. https://www.whitehouse.gov/fact-sheets/2025/04/fact-sheet-president-donald-j-trump-closes-de-minimis-exemptions-to-combat-chinas-role-in-americas-synthetic-opioid-crisis/

White House. (2025, July). Fact sheet: President Donald J. Trump suspends the de minimis exemption for commercial shipments globally. https://www.whitehouse.gov/fact-sheets/2025/07/fact-sheet-president-donald-j-trump-is-protecting-the-united-states-national-security-and-economy-by-suspending-the-de-minimis-exemption-for-commercial-shipments-globally/

World Customs Organization. (2025). The Norwegian VOEC scheme and low-value imports. https://mag.wcoomd.org/magazine/wco-news-108-issue-3-2025/the-norwegian-voec-scheme/